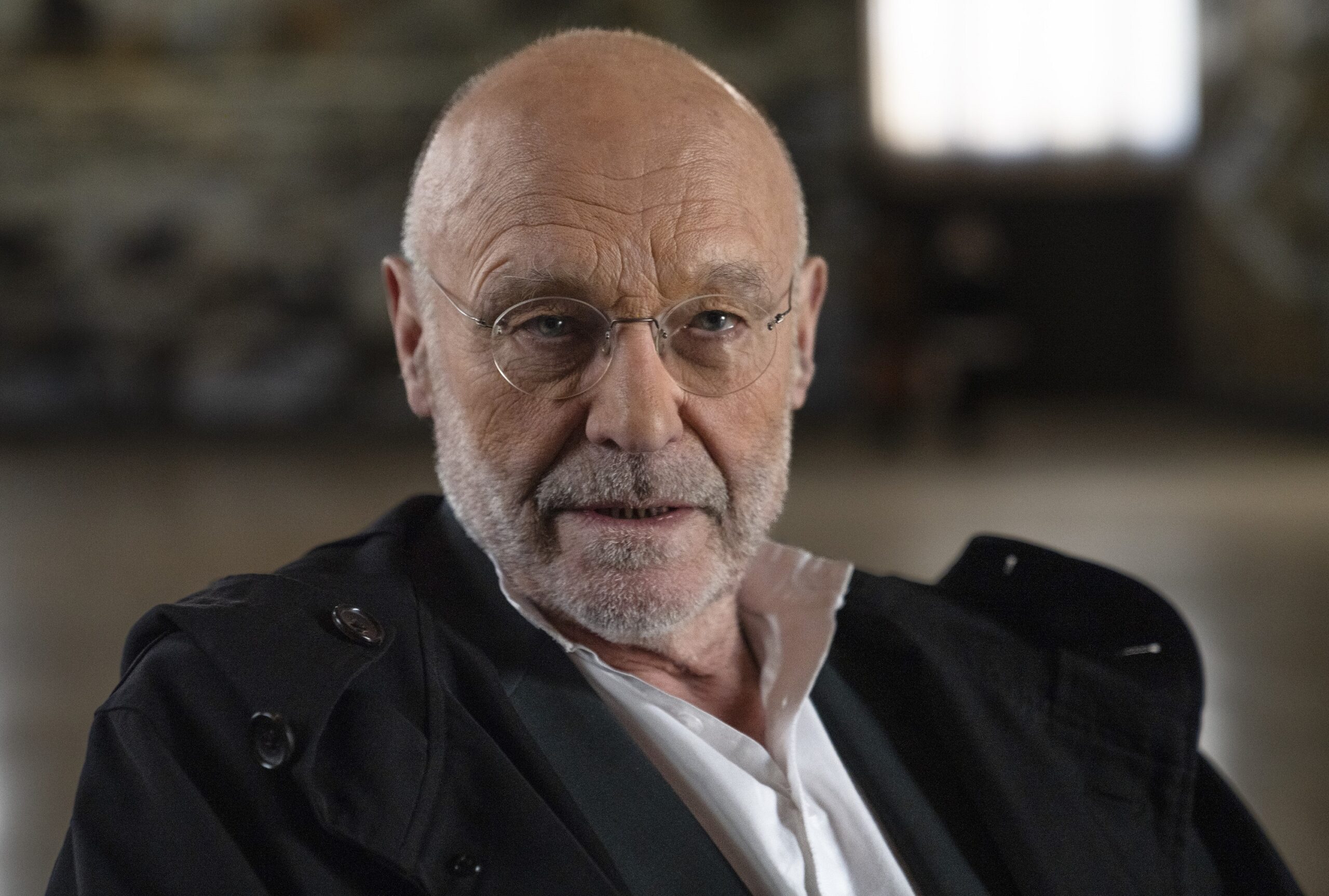

Anselm Kiefer

Anselm Kiefer was born in Donaueschingen, Germany, and has lived and worked in France since 1991. He is regarded, alongside Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, and Georg Baselitz, as one of the leading German artists of his generation. Paintings, collages, photographs, and books made of lead are among the elements in his expanding artistic cosmos, which finds expression through unconventional and symbolically charged materials. Across forty years, in works ranging from somber interiors and wasted landscapes to cosmic horizons, Kiefer has explored sensitive historical subjects, and is probably best known for having taken as one of his themes the foremost taboo in modern Germany: the Second World War. Kiefer’s work gained wide recognition in the early 1980s, at a time of postmodern fascination with historical subjects, the spread of Neo-expressionism, the revival of painting, and an increasing level of interest in contemporary German art. His creative expression was, however, born out of conceptual and process art. He studied in Düsseldorf under the painter Peter Dreher, with Joseph Beuys as an informal mentor. Kiefer’s work is often in dialogue with history, as was Beuys’, and his conceptual background is evident in his emphasis on the literary and the textual. His titles are often written in large letters across the canvas, opening for a reading of the painting as both an image and a concept – as fragments of language. One of Kiefer’s most famous series of paintings, Margarete and Shulamite (1980–81), references the poem Death Fugue (Todesfuge) by Paul Celan, a survivor of the Nazi concentration camps. The work for which he first became known was a controversial series of photographs in which he is depicted making a Nazi salute at various locations in France, Switzerland, and Italy. He followed this up with paintings during the 1970s and 80s referencing German and Christian legends, Wagner, and National Socialist architecture. By the mid-1980s he had turned to more universal themes derived from the ancient civilizations of the Middle East and Mesopotamia, and later from a fascination with alchemy and the Kabbalah. True to Beuys’ spirit, Kiefer saw parallels between the roles of the alchemist and the artist, the latter transforming raw materials and canvas into conveyors of symbolic meaning. Opposing forces meet head to head in Kiefer’s works: heaven and earth, order and chaos, civilization and nature, individual and history, material and spiritual, landscape and architecture. Through overlapping layers, woven together on the surface of his canvas, Kiefer carries out his own form of cultural archaeology, where the predominant theme is history as a fluid and active phenomenon. He is concerned with the ways in which the present is influenced by the past, and with how our perception of history is always shifting. Ancient mythological and astronomical traditions, and philosophical and theoretical systems, rise to the surface of his thick impasto mixed with straw, sand, earth, hair, tile dust, flowers, and lead. It is difficult to remain indifferent to Kiefer’s monumental works. Their surfaces tell not only of their coming into being, but also of their inevitable disintegration. Pervading his art, like a minor key, is the reminder that all civilization will decay. The sheer weight of the material can feel overwhelming, and the works give the impression that at any moment they might crumble into dust. Kiefer’s narratives are equivocal, giving rise to a wide range of interpretations. His works have variously been described as ambivalent breaks with taboo, as a grief process through painting, and as a revival of mythological themes. He can in no way be accused of underestimating his public, for much of his output can only be fully appreciated by those with an in-depth knowledge of literature and history. But it is precisely this deep seriousness that engages and fascinates people all over the world. At the same time, Kiefer’s art seems full of wonderment, mystery, and dreams, and a longing to understand the unfathomable.